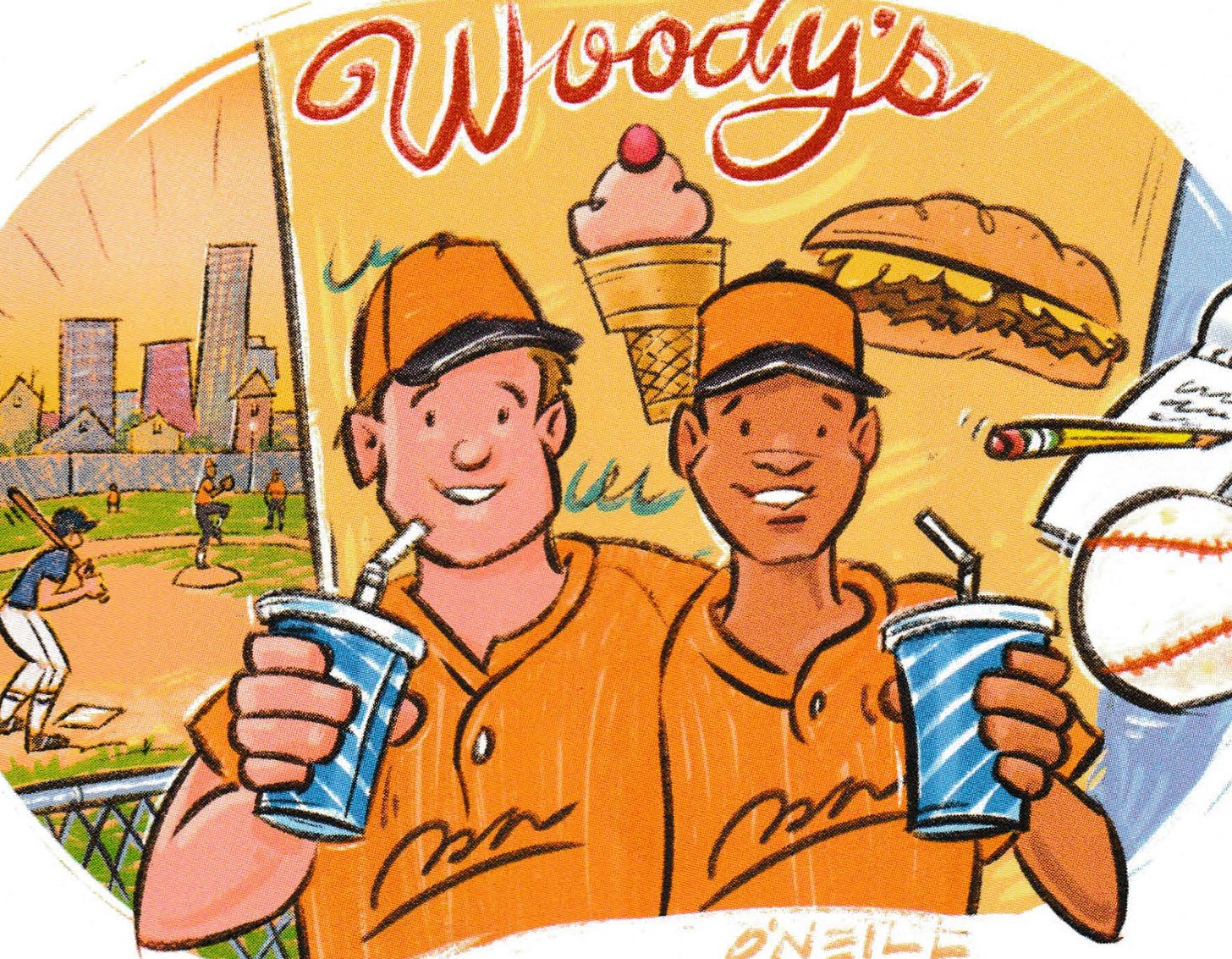

Illustration by Gerry O’Neill

………………………….

I HEAR A VOICE and look up.

The face is much older, the voice deeper. But both are so familiar. "Hey,Coach," says Peter Gay, giving me what I used to call his sly fastball grin. I stand up and we hug.

"You grew up, buddy," I say.

'And you grew old, Coach."

“Funny how that happens."

We both laugh. Forty years ago, Pete and his brothers, Fred and Rodney, and their friend, Alvin, were the invincible infield of an inner city baseball team I coached for two spring seasons called the Highland Park Orioles. I nicknamed them the Birds of Paradise because most of the players came from a tough inner city neighborhood where, by agreement with their anxious parents and guardians, I dropped them off after games near a street named Paradise.

Atlanta, in those years, was anything but a paradise. Due to the infamous "Missing and Murdered" crisis that besieged the city between 1979 and 1981, in which 30 Black kids and young adults were abducted and murdered by an unknown person or persons, the city that declared itself "too busy to hate" earned the distinction of being the "Murder Capital of America" for several years running.

Looking back, going out at my editor's suggestion to write a sweet little feature story about the hopefulness of spring baseball tryouts in my Midtown neighborhood and getting strong-armed by a frantic league director to take on a wild bunch of Orioles whose coach never bothered to show up was one of the most fortunate things that ever happened to me.

In the spring of 1982, I was the senior writer of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution Sunday Magazine, the oldest Sunday magazine in the nation, where Margaret Mitchell worked when she wrote Gone with the Wind. During my six years there, I'd written about everything from unrepentant Klansmen to corrupt politicians, presidential campaigns to repo kings, a constant stream violence and social mayhem.

Approaching age 30, I’d decided that I was rapidly becoming a career burn out case. In a nutshell, I'd had enough of covering the sorrows of my native South.

An early tipping point came while working on a story about Atlanta's famed medical examiner, Dr. Robert Stivers - reportedly the inspiration for the hit TV show, Quincy - when I actually saw my next-door neighbor, a med student, gunned down in his darkened backyard doorway by an assailant. The young man died as his hysterical girlfriend and I waited for the EMTs and cops to arrive. The cops took their own sweet time, shrugging it off as just another drug deal gone sideways. I followed the ambulance hauling my neighbor's body downtown to the ME's office to await his autopsy. Talk about art imitating life's worst moments.

My editor, a charming true-blue Atlantan named Andy Sparks, who'd been on the magazine since the days of Margaret Mitchell, had spotted my brewing crisis and suggested I write about "lighter" subjects for a time. So, I went over to the rutted ball field in Highland Park with pen and pad and not a lot of hope in hand. The last thing I expected was to be Shanghaied into become a youth baseball coach.

Our first practice was pure chaos. The team horsed around and barely paid attention as I placed them into tentative playing positions. Somehow,I managed to get the four best players into key spots. Pete and Alvin would rotate between pitching and playing third; Fred at first base, and Rodney catching. On the way home, I stopped at a popular neighborhood joint called Woody's just two blocks from the ball field, foolishly thinking that if I bought them a milkshake and got to know them better, the four best players on the team might help me whip the Birds into shape. Instead, they hooted and hollered and made such a rude ruckus that the owners tossed us out and warned us not to come back unless we could learn to behave.

"I remember how you gave us a lecture about being gentlemen in public places," Pete says as we sit together at Woody's 40 years later. The place is now owned by a black couple. Its milkshakes and steak-and-cheese sandwiches are better than ever. Peter Gay is 53 today, a hard-working father of three grown children, and a popular volunteer football coach and recruiter for Booker T. Washington High in the center city. He's dressed in the bright blue colors of the Washington Bulldogs.

Two years before, he called me out of the Bulldog blue. "I remembered the story you wrote for the Reader's Digest about us," he explained that afternoon, “and I remembered that you left Atlanta to write books. That's how I found you on the internet."

"Tell me," I said. "Is Woody's still there?" A day later, Pete sent me a photo of himself in front of the Woody's sign. We made a plan to meet there when I came to Atlanta for my latest book research.

That first season, the Birds of Paradise never lost a game. Or if we did, I don't recall it. We often won by football scores, easily claiming the Midtown Youth Baseball Championship. Pete had a lethal fast ball. Alvin's curve was almost un-hittable. Rodney was an awesome catcher and Fred played first base like a pro. Even better, the Birds calmed down and became true gentlemen on and off the field, though I spent a small fortune on milkshakes once the other members of the team learned about my gambit and got in on the post-game treat.

"You kind of bribed us to behave with milkshakes," Peter . "But I get that now. It really worked."

Because of the Birds, I stayed for one more spring in Atlanta. In year two we went undefeated.

The owners of Woody’s even threw us a party providing milkshakes and cheese steaks on the house. My guys were perfect gentlemen.

Days later, a coach from an all-white team in the northern suburbs even phoned me to propose a "Metro" championship game at his team's immaculate facility north of the city. We set a date for the game, and I went out and purchased new Oriole jerseys with the names of my kids on the back.

A few days before the match-up, however, my opposing coach called back to say that some of his parents of his championship team were “concerned” that my kids might feel "intimidated about playing in such a nice facility." I assured him the Birds wouldn't be intimidated. We both knew the meaning of his words.

"Well," he said uneasily, "maybe ... next year."

There was no next year. A short time later, I left Atlanta for Vermont, where I hoped to become a fly-fishing guide, knocked the rust off my golf game and found a whole new career – and happiness - writing about people and subjects that enrich life.

I also realized that the Birds of Paradise had given me a gift over those two final seasons that helped me find my groove as a writer - a healing glimpse of what real happiness is like.

Over the years I've seen Pete and Rodney several times and even attended the beautiful wedding of Pete's daughter, Petera, a few summers ago.

Sadly, word recently reached me the other day that Peter suffered a devastating stroke last October.

I immediately phoned him, learning from his older brother John that he’s slowly recovering the use of his legs and voice.

Peter and I spoke for only a few minutes. He spoke with some difficulty but he still called me “Coach.”

I promised to come see him soon.

And I will.

He was my favorite Bird of Paradise. I long to see him fly again soon.