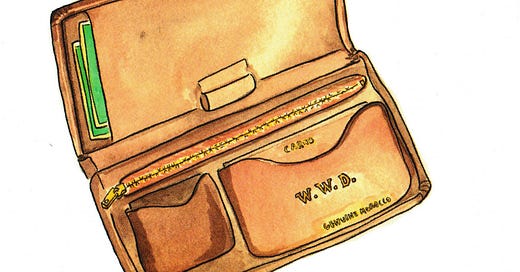

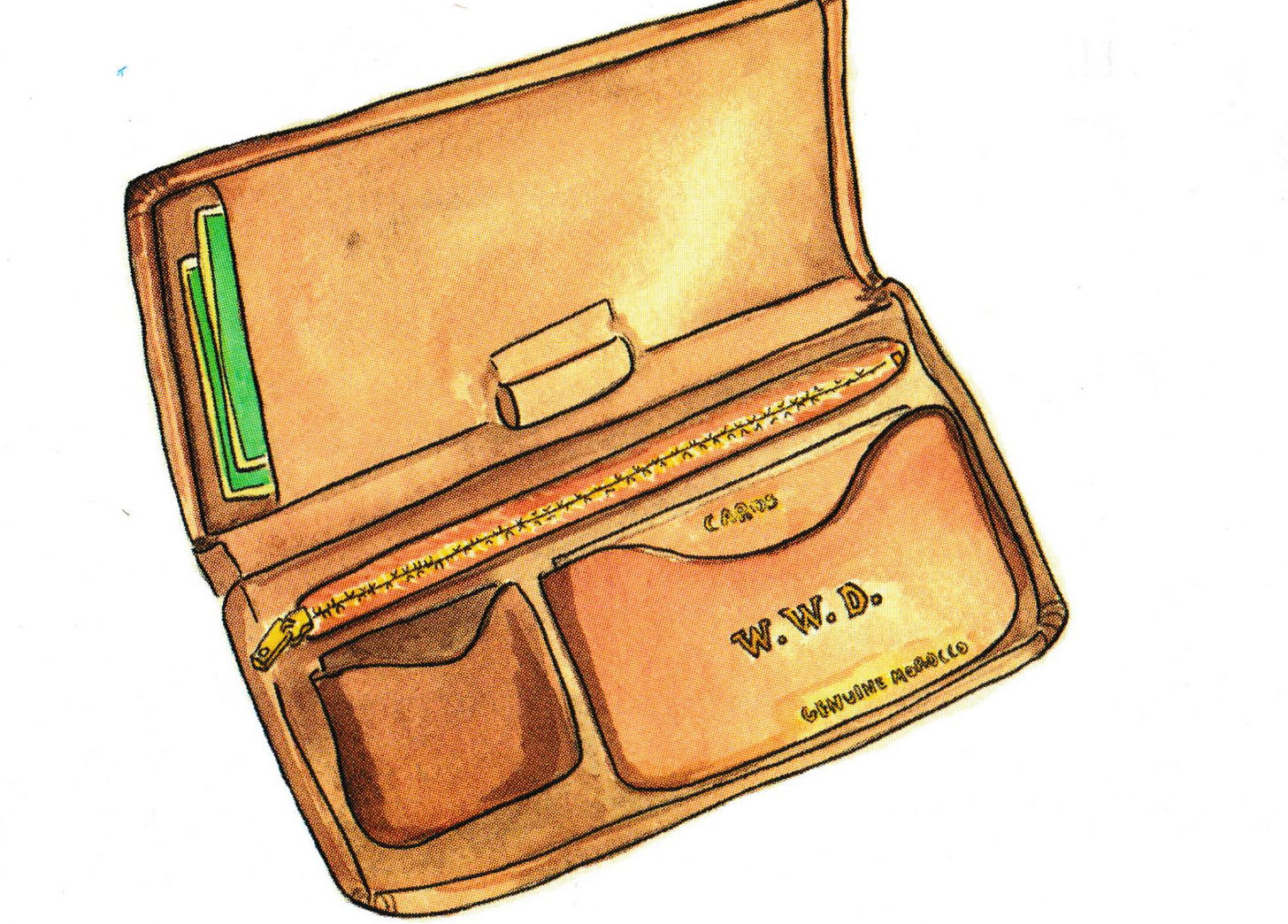

Artwork by Gerry O’Neill

NOT LONG AGO, while cleaning out a desk drawer that I should have cleaned out donkey years ago, I found a simple but beautifully made, old-fashioned, full-grain leather breast pocket wallet with the initials "W.W.D." embossed in gold leaf inside.

It looks brand-new and essentially is, though it was made sometime in the early 1940s. My father gave me this wallet in 1995 while we were on a golf trip to England and Scotland to play the golf courses where he learned to play the game as a trained glider pilot on the Lancashire coast during the Second World War. The wallet originally belonged to my grandfather, William Walter Dodson, a gift from his father to him upon his return from the war in the early summer of 1945, when my grandparents took a train from their farm in North Carolina to meet my dad returning to New York Harbor on the Queen Elizabeth.

According to family lore, it was the only visit they - Walter and Beatrice Dodson - ever made to New York City. My mother met them there, dolled up to look like Veronica Lake and fresh from her job working for an admiral in Annapolis, or as she described it, “being chased around the desk by a brass admiral.”

She was indeed a beauty, the youngest of eleven children from the hills of West Virginia and a former Miss Western Maryland who up and ditched a rich guy named Earl who drove a Stutz Bearcat before the war in order to marry my father shortly before he enlisted. While my dad was away, the singer Tony Martin offered her a job singing with his orchestra, but my strong-willed Southern Baptist grandmother quickly put the clamps on that idea. My dad purchased this handsome wallet for his father somewhere in London's Covent Garden, I learned decades later, and a dozen bottles of French perfume for his Liberty Bride after the liberation of Paris, hidden in the bottom of his military footlocker to get past customs officials.

I have no idea what he brought his mother. Real English tea, perhaps. The story I always heard was that they all went to Toots Shore's restaurant on 51st Street for supper that night but couldn't get in for all the jubilant Gls and their gals - settling, in the end, for pastrami sandwiches at the Carnegie Delicatessen. My grandparents, farm people, reportedly turned in early at their modest hotel, and my dad took his bride to a Broadway show.

My dad tried to give me this wallet for the first time on the day of my grandfather's funeral in 1966. I suppose he reasoned that because I was named for both my grandfathers - Walter is my middle name - I might wish to have it as a keepsake of its quiet-spoken owner.

But he was wrong about that. I was 13 and didn't see the point of carrying around a dead man's barely used wallet, though even then I recognized its fine craftsmanship, hand-sewn from Moroccan leather, with a fine brass zippered compartment and even an ingenious little slot containing a leather square marked "stamps," a relic from a time when a letter home really meant the world.

Then there were the three beautiful initials in gold lea£ I did love my grandfather, you must understand, even if I didn't fully grasp his peculiar ways, his calm and protracted silences and natural simplicity of motion. By the time I really got to know him, Walter Dodson had given up his farm in Guilford County and moved with my grandmother to a small cinderblock house surrounded by rose bushes and dusty tangerine trees on the shores of Lake Eustis in central Florida. I hated going there for Christmas. No place on Earth could possibly have been slower and more boring to my churning pre-teen brain. And yet ... Walter took me bass fishing in his skiff and showed me how to cast a spinning lure and, later, in his modest carport, taught me how to cut a proper straight line with a hand saw and hammer a nail without smashing my thumb or finger. He smoked cheap King Edward cigars and sometimes hummed what sounded to me like church hymns, though he never went to church when my Baptist grandmother did. William Walter Dodson headed straight for his garden.

Mind you, I was never uncomfortable in my grandfather's presence - in fact, quite the opposite. Though I couldn't have begun to put it into words at those moments on those silent bayou waters, he struck me as a man who loved being outdoors all the time, either tying his tackle lines or snipping his roses or hoeing in his vast vegetable garden or just sitting in his ancient wooden carport chair listening to what my older brother Dickie and I mockingly called "redneck string music" on his Philco radio as the crickets sang on his lawn and fireflies danced in the tangerine trees. Astonishingly to us, our grandparents didn't even own a TV set.

After Walter's sudden death, after I declined to accept the gift of his wallet, my father placed his father's wallet in his office desk, where it stayed for the next thirty years. He brought it along with us to Britain for what would turn out to be our final golf trip together and offered it to me, almost off-handedly one evening as we were having supper in a pub in St. Andrews.

By then I had a very different understanding and appreciation of my "simple" Southern grandfather. He was rural polymath and carpenter who never got beyond the third grade but had a gift for making anything with his hands.

During the 1920s, he worked on crews erecting the state's first rural electrification towers, for instance, and returned to Greensboro just in time to serve as a foreman on the crew wiring the Jefferson Standard Building, the state's first "sky-scraper."

Walter's famously calm demeanor suddenly made sense. His mother, “Aunt” Emma, my father's grandmother, I’d learned by that point, was a full-blooded Catawba or Cherokee woman who was known for her natural remedies along Buckhorn Road between Hillsborough and Carrboro.

My father spent his earliest summer days on Aunt Emma's farm, accompanying this gentle Native American woman on her daily plant-gathering walks over the fields of the original Dodson home place. Walter, the oldest of her four sons and two daughters, clearly identified with his lost Indian ancestry - as did, to some extent, my own father.

Today, the old family homestead is an upscale housing development. But like Walter's surviving wallet, nothing important is really ever lost. One of the first adventures our father took my brother and me on as small boys was to hunt for buried arrowheads at the Town Creek Indian Mound in the ancient Uwharrie Hills. When we began camping and fishing in the Blue Ridge Mountains, be always took a bag of useful books along to read - a hodge-podge of titles ranging from Kipling's Just So Stories to the works of Sir Walter Scott - which be called, tellingly, his "Medicine Bag."

William Walter Dodson, I came to learn, was a man from another time and place who knew the simple pleasures and abiding peace of the natural world. His own kindness wasn't showy but genuine. During the Great Depression, whenever someone down on their luck showed up at his back door seeking help, according to my father and other family members, Walter would feed him and provide a bed in a spare but clean room behind his barn. Skin color was irrelevant.

My Southern Baptist grandmother, though something of a social butterfly who preached the value of book-learning, wasn't nearly so naturally generous of spirit. Somewhere in our voluminous family scrapbooks is a faded snapshot of Walter standing beside a black man I only knew as "Old Joe" who lived in that room and helped out on the farm for years. No one knows his real name but it hardly matters. Reportedly, Walter and "Old Joe" were close friends for many years.

Save for my own fading memories and a rusted twenty-two rifle and this handsome wallet from Covent Garden - still looking almost as new as that day my father gave it to his father in New York City half almost a century ago - that's about all l have left of my paternal grandfather, the dignified fellow who taught me to fish in a bayou and saw a straight line and - more importantly -savor the healing quiet of nature.

I tell myself Walter never had enough money to really need such a fine wallet, which may explain its excellent condition. But that's only speculation on my part. The older I get, the more I appreciate the rhythms of WW's simple lifestyle.

By contrast, my modern life seems anything but simple. Which may explain why, going forward, I write this Simple Life column every month — a chance to remind myself of the ordinary gifts of life that are overlooked in the rush of an ordinary day.

Someday I may passing Walter’s wallet along to my son Jack, a gifted journalist and filmmaker who has lived abroad for many years writing about the injustices of this world.

Perhaps he’ll want it — or maybe think it too old fashioned for his modern life on the go.

Only time will tell will tell. In the meantime, I’ll keep my grandfather’s fancy leather wallet in my desk, close to my heart and memories of the quiet man who I seem to be more like with each passing year.

Hi Jim,

We met several years ago when Greensboro Country Club reopened the Farm Course after a renovation project. You were kind to spend time with the membership discussing your book, The Range Bucket List. Each member left with a copy of the book, and your participation added greatly to the day.

After reading Walter’s Wallet, I felt compelled to tell you how that struck close to home. My dad passed away at 39-years old, when I was in college. The older I get (now 56), the more I cherish the mementos that now mean so much to me. His gold plated initials that he wore on the collar of his dress shirts, or his Boy Scout leader cap with pins from other Scout troops he traded with - all sweet memories of a man that meant so much to me.

We return to Greensboro often, as our oldest daughter and son-in-law have settled there. When I go to her office building (DMJ) I remember it was the site of the Green Valley Golf Club - first learning of the course’s legacy by reading about it in Final Rounds.

Here’s to One Man’s Simple Life. Thank you for the gift of reading your work.

With much gratitude,

Bud